The keys to long-term success are professional management and keeping the family committed to and capable of carrying on as the owner.

Family businesses are an often overlooked form of ownership. Yet they are all around us—from neighborhood mom-and-pop stores and the millions of small and midsize companies that underpin many economies to household names such as BMW, Samsung, and Wal-Mart Stores. One-third of all companies in the S&P 500 index and 40 percent of the 250 largest companies in France and Germany are defined as family businesses, meaning that a family owns a significant share and can influence important decisions, particularly the election of the chairman and CEO.

As family businesses expand from their entrepreneurial beginnings, they face unique performance and governance challenges. The generations that follow the founder, for example, may insist on running the company even though they are not suited for the job. And as the number of family shareholders increases exponentially generation by generation, with few actually working in the business, the commitment to carry on as owners can’t be taken for granted. Indeed, less than 30 percent of family businesses survive into the third generation of family ownership. Those that do, however, tend to perform well over time compared with their corporate peers, according to recent McKinsey research. Their performance suggests that they have a story of interest not only to family businesses around the world, of various sizes and in various stages of development, but also to companies with other forms of ownership.

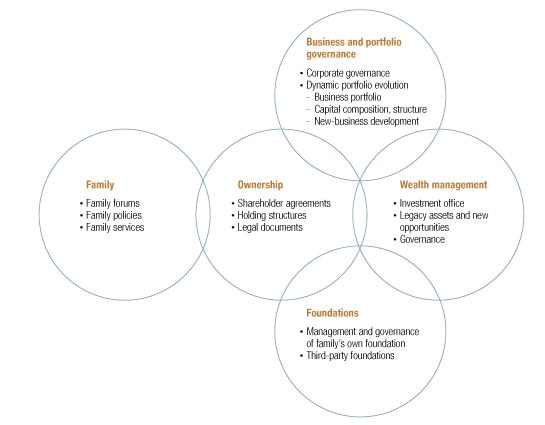

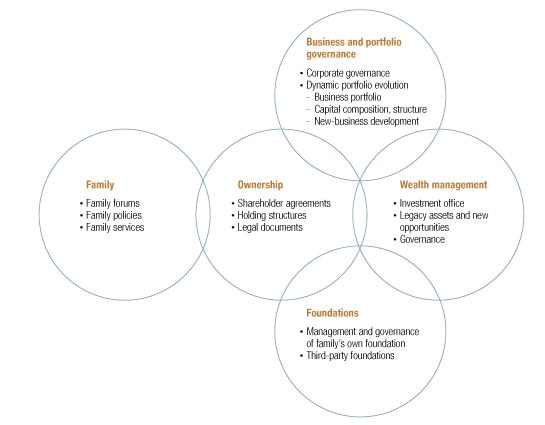

To be successful as both the company and the family grow, a family business must meet two intertwined challenges: achieving strong business performance and keeping the family committed to and capable of carrying on as the owner. Five dimensions of activity must work well and in synchrony: harmonious relations within the family and an understanding of how it should be involved with the business, an ownership structure that provides sufficient capital for growth while allowing the family to control key parts of the business, strong governance of the company and a dynamic business portfolio, professional management of the family’s wealth, and charitable foundations to promote family values across generations (Exhibit 1).

Five dimensionsFor a family business to be successful, five dimensions of activity must be working well and in synchrony.

Family businesses can go under for many reasons, including family conflicts over money, nepotism leading to poor management, and infighting over the succession of power from one generation to the next. Regulating the family’s roles as shareholders, board members, and managers is essential because it can help avoid these pitfalls.

Large family businesses that survive for many generations make sure to permeate their ethos of ownership with a strong sense of purpose. Over decades, they develop oral and written agreements that address issues such as the composition and election of the company’s board, the key board decisions that require a consensus or a qualified majority, the appointment of the CEO, the conditions in which family members can (and can’t) work in the business, and some of the boundaries for corporate and financial strategy. The continual development and interpretation of these agreements, and the governance decisions guided by them, may involve several kinds of family forums. A family council representing different branches and generations of the family, for instance, may be responsible to a larger family assembly used to build consensus on major issues.

Long-term survivors usually share a meritocratic approach to management. There’s no single rule for all, however—policies depend partly on the size of the family, its values, the education of its members, and the industries in which the business competes. For example, the Australia-based investment business ROI Group, which now spans four generations of the Owens family, encourages family members to work outside the business first and gain relevant experience before seeking senior-management positions at ROI. Any appointment to them must be approved both by the owners’ board, which represents the family, and the advisory council, a group of independent business advisers who provide strategic guidance to the board.

As families grow and ownership fragments, family institutions play an important role in making continued ownership meaningful by nurturing family values and giving new generations a sense of pride in the company’s contribution to society. Family offices, some employing less than a handful of professionals, others as many as 40, can bring together family members who want to pursue common interests, such as social work, often through large charity organizations linked to the family. The office may help organize regular gatherings that offer large families a chance to bond, to teach young members how to be knowledgeable and productive shareholders, and to vote formally or informally on important matters. It can also keep the family happy by providing investment, tax, and even concierge services to its members.

Maintaining family control or influence while raising fresh capital for the business and satisfying the family’s cash needs is an equation that must be addressed, since it’s a major source of potential conflict, particularly in the transition of power from one generation to the next. Enduring family businesses regulate ownership issues—for example, how shares can (and cannot) be traded inside and outside the family—through carefully designed shareholders’ agreements that usually last for 15 to 20 years.

Many of these family businesses are privately held holding companies with reasonably independent subsidiaries that might be publicly owned, though in general the family holding company fully controls the more important ones. By keeping the holding private, the family avoids conflicts of interest with more diversified institutional investors looking for higher short-term returns. Financial policies often aim to keep the family in control. Many family businesses pay relatively low dividends because reinvesting profits is a good way to expand without diluting ownership by issuing new stock or assuming big debts.

In fact, some families decide to shut external investors out of the entire business and to fuel growth by reinvesting most of the profits, which requires good profitability and relatively low dividends. Others decide to bring in private equity as a way to inject capital and introduce a more effective corporate governance culture. In 2000, for example, the private-equity investor Kohlberg Kravis Roberts gave Zumtobel, the Austria-based European market leader for professional lighting, a capital infusion (KKR exited in 2006). Such deals can add value, but the downside is that they dilute family control. Others take the IPO route and float a portion of the shares. An IPO can also be a way to provide liquidity at a fair market price for family members wanting to exit as shareholders.

To keep control, many family businesses restrict the trading of shares. Family shareholders who want to sell must offer their siblings and then their cousins the right of first refusal. In addition, the holding often buys back shares from exiting family members. Payout policies are usually long term to avoid decapitalizing the business.

Because exit is restricted and dividends are comparatively low, some family businesses have resorted to “generational liquidity events” to satisfy the family’s cash needs. These may take the form of sales of publicly traded businesses in the holding or of sales of family shares to employees or to the company itself, with the proceeds going to the family. One chairman said of his company, “Every generation has a major liquidity event, and then we can go on with the business.”

With clear rules and guidelines as an anchor, family enterprises can get on with their business strategies. Two success factors show up frequently: strong boards and a long-term view coupled with a prudent but dynamic portfolio strategy.

Large and durable family businesses tend to have strong governance. Members of these families avoid the principal–agent issue by participating actively in the work of company boards, where they monitor performance diligently and draw on deep industry knowledge gained through a long history. On average, 39 percent of the board members of family businesses are inside directors (including 20 percent who belong to the family), compared with 23 percent in nonfamily companies, according to an analysis of the S&P 500. 1 1. Ronald C. Anderson and David M. Reeb, “Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500,” The Journal of Finance, 2003, Volume 58, Number 3, pp. 1301–27. “The family is a true asset to the management team, since they have been around the industry for decades,” said the CEO of a family business. "Still, they separate ownership and management in a good way.”

Of course, it’s important to complement the family’s knowledge with the fresh strategic perspectives of qualified outsiders. Even when a family holds all of the equity in a company, its board will most likely include a significant proportion of outside directors. One family has a rule that half of the seats on the board should be occupied by outside CEOs who run businesses at least three times larger than the family one.

Procedures for all nominations to the board—insiders as well as outsiders—differ from company to company. Some boards select new members and then seek consent by an inner family committee and formal approval by a shareholder assembly. Formal mechanisms differ; what counts most is for the family to understand the importance of a strong board, which should be deeply involved in top-executive matters and manage the business portfolio actively. Many have meetings that stretch over several days to discuss corporate strategy in detail.

Family businesses, like their nonfamily peers, face the challenge of attracting and retaining world-class talent to the board and to key executive positions. In this respect, they have a handicap because nonfamily executives might fear that family members make important decisions informally and that a glass ceiling limits the career opportunities of outsiders. Still, family businesses often emphasize caring and loyalty, which some talented people may see as values above and beyond what nonfamily corporations offer.

Successful family companies usually seek steady long-term growth and performance to avoid risking the family’s wealth and control of the business. This approach tends to shield them from the temptation—which has recently brought many corporations to their knees—of pursuing maximum short-term performance at the expense of long-term company health. A longer-term planning horizon and more moderate risk taking serve the interests of debt holders too, so family businesses tend to have not only lower levels of financial leverage but also a lower cost of debt than their corporate peers do (Exhibit 2).