Teachers’ knowledge of each child helps them to plan appropriately challenging environments and activities that are tailored to the children’s strengths and needs. Assessing children regularly is essential to build that individualized knowledge—and to identify children who may benefit from more specialized supports. This article offers practical tips for you to engage in systematic, observation-based assessment by keeping anecdotal records on each child.

With so many required assessments, it’s understandable why the word itself may bring up negative feelings for teachers. But understanding the different types of assessment and how you can use them to support your reflection and planning is important.

High-stakes summative assessments are used to gauge children’s learning against a standard or benchmark. Summative assessments are often given at the end of the year and are sometimes used to make important educational decisions about children.

In contrast, formative assessments are ongoing and tend to be based on teachers’ intentional observations of children during specific learning experiences. Many teachers find formative assessments most useful when planning learning experiences, activities, and environments. Your notes about what children are able to do while they engage in real-life tasks such as block building, retelling a story, or climbing on a playground structure provide a wealth of information. Getting started with the quick, easy strategies in this article will help you develop a system for taking useful notes. These notes will ground your teaching decisions and enrich children’s portfolios with examples of their everyday learning.

Anecdotal records are brief notes teachers take as they observe children. The notes document a range of behaviors in areas such as literacy, mathematics, social studies, science, the arts, social and emotional development, and physical development. When recording observations, it’s important to include a concrete description and enough details to inform future teaching strategies. For example, a statement such as “The student was on task” provides no information about the task or the behavior, but a statement like “The student built a tower from colored cubes, creating an AB pattern after looking at a card that showed a similar alternating pattern” provides concrete evidence.

To avoid vague notes, list the associated learning center or subject area and include a specific description of what the child is doing. Of course, time is always a concern in preschool classrooms, and children move quickly from one task to the next! Abbreviations can help capture detailed observations in an efficient way.

For example, instead of stating, “Leah uses inventive spelling,” an anecdotal note could include an abbreviation for the center Leah is playing in and evidence of her inventive spelling: “Leah—DP [dramatic play center]—Wrote grocery list: BACN, aGS, sreL.” (If time is short, Leah’s teacher could also take a photo of Leah’s writing and embed it along with the anecdotal record in Leah’s portfolio.) The evidence in Leah’s note gives insight into the consonants and vowels she is learning and the letter forms she can produce. It also aids the teacher in better understanding Leah’s progress on the continuum toward standard spelling, helping her be more informed about how to support Leah instructionally.

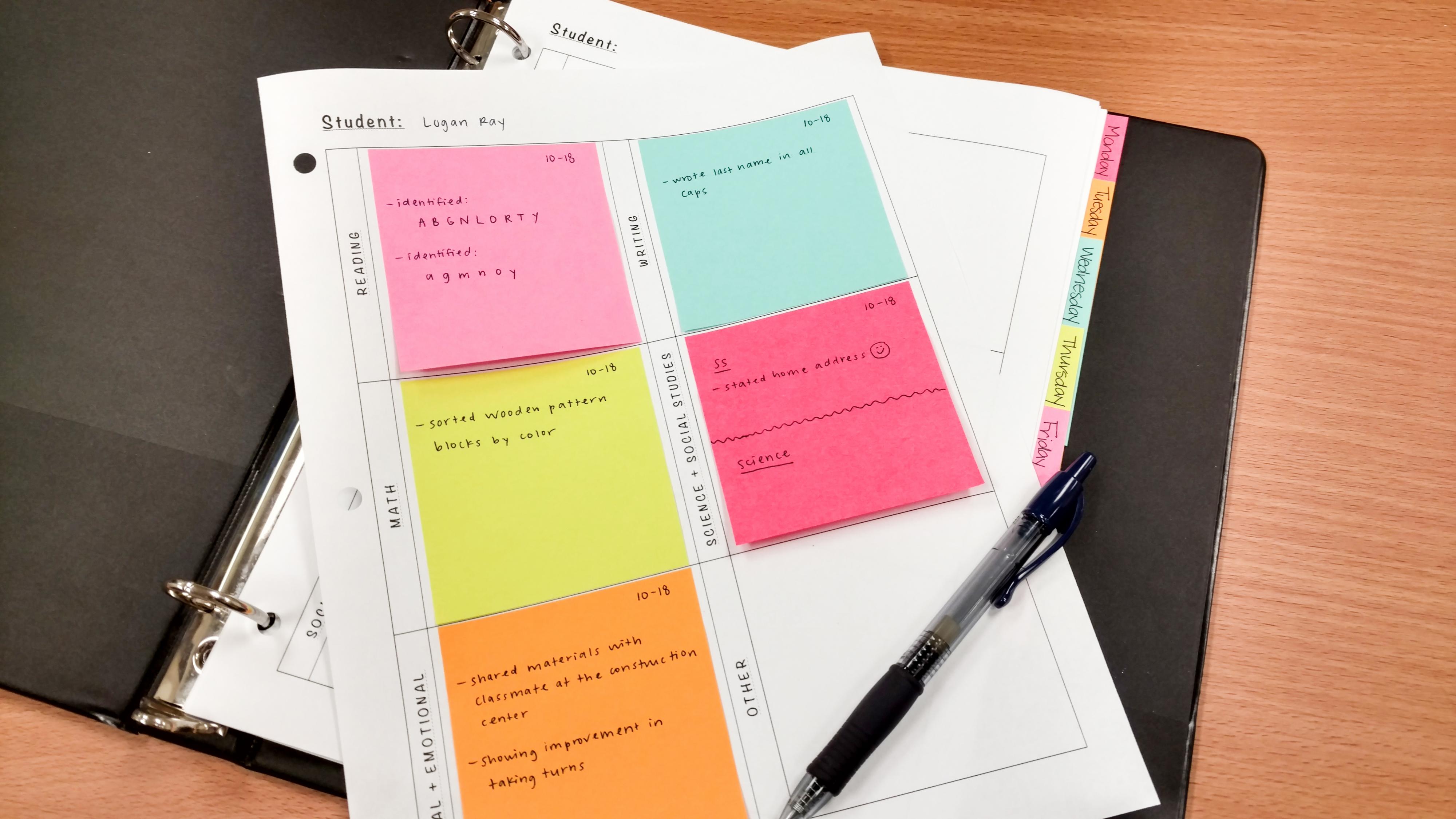

When taking anecdotal records, it’s important to consider word choice. Statements that begin with words like can’t or doesn’t promote a deficit view and do not support future instructional planning. For example, the statement “Logan doesn’t identify all his letters” is very different from “Logan identifies the uppercase letters A, B, G, N, L, T, Z.” Writing what children can do ensures that instructional decisions are grounded in children’s strengths.

It’s easy to draw conclusions about a child, especially when you have a history with the family, such as previously teaching a sibling. But no two children are exactly alike, even if they share the same family, community, or culture. Familiarity with children and families may make it easier for you to develop the home–school connection, but it shouldn’t affect how you view or treat a child. Similarly, familiarity with a child’s community or culture may give you helpful context, but it should not lead to making assumptions—positive or negative. Anecdotal records are intended to be neutral observations of a child’s behaviors and interactions, so it’s important to guard against assumptions and biases.

It’s helpful to periodically review your notes to look for examples of bias. To do this, reflect on ways the notes have been written to see if they’re objective. Then look for patterns in the notes to see if subjective comments are linked to any one child or to a group of children. Identifying these patterns can help reveal unconscious assumptions and can assist in writing more objective notes in the future. You can also ask a trusted colleague to review your notes for the same purposes.

Daily anecdotal notes can be quick to write and easy to file and organize. They should also serve as the basis for reflective practice.

Be selective about the behaviors you observe. Having a specific focus can help you pay attention to the most important details during observations, making your anecdotal records more useful for planning or for individualizing future instruction. In addition, it removes the unreasonable expectation of documenting everything for every child every day.

One suggestion for getting started is to divide the class into small groups of about five students. Assign each group a day of the week, and then concentrate on observing just those five students on their assigned day. These daily focus groups are a good way to organize and manage record keeping—and they prevent children from slipping through the cracks. Here are a couple examples of anecdotal record-keeping systems that use daily focus groups.

A Post-it notebook uses a form for each child that has six boxes. Teachers often choose to label the boxes Reading, Writing, Math, Science/Social Studies, Social/Emotional, and Other, but the form can be tailored to highlight any content areas or learning domains that you choose! As you make observations, record them on a sticky note and place it on a clipboard. At the end of the day, transfer the notes to the child’s form in the appropriate category. Keep the forms in a three-ring binder with dividers separating each daily focus group, or organize the forms alphabetically.

The index card system uses individual index cards color-coded by daily focus group (for example, Monday’s group is assigned green index cards, Tuesday’s group is yellow). Use a binder clip to keep each group’s index cards together, then use the cards throughout the day as you capture and record observations on group members’ individual cards. At the end of the day, file the cards in a box, and then pull the cards for the next day.

You may choose to record literacy behaviors (or any other content area you’re emphasizing) on one side of the card and math behaviors (or another content area) on the other side. Additional cards can be used to capture behaviors in other areas, or a card can be subdivided. Once a child’s card is full, issue a new one. You can also easily take the cards outdoors when observing and recording children’s social interactions on the playground.

A manageable system (like those described earlier) makes it easy to collect the information you need to reflect about what the children are learning. Reflection and anecdotal notes should be tightly linked and should serve as the foundation for instructional planning, helping you think more deeply about children’s growth and learning. Also, reflecting on these records allows you to generate questions and hypotheses that fuel additional observations and anecdotal records.

Adopting a child-centered approach to assessment helps you view students from a strengths-based perspective and match teaching to individuals’ needs. As a result, children receive more tailored instruction as you become better informed about each child’s progress. Reflecting on anecdotal notes can also help you with grouping decisions. Small groups in the classroom should be flexible, and using observational data can assist you in re-forming groups to mirror children’s changing needs.

You may find it useful to write out your reflections and add them to a child’s collection of anecdotal records; as months go by, being able to review both anecdotal notes and timely reflections can be very informative. The information collected from the anecdotal records can also be transferred to more formal assessments, like developmental checklists.

When a challenging situation arises, such as a child not making progress as expected, you can share your notes and reflections with colleagues to generate new ideas about lessons and activities to try. And if a comprehensive or diagnostic assessment seems called for, you have a rich set of records to share with families and specialists.

Anecdotal notes are also a great source of information when meeting with a family. During a family conference, you can use ancecdotal notes to provide the family with concrete examples of their child’s learning and development and give them insight into their child’s school day. The information can also assist in communicating to families the variety of ways they can support their child at home. Additionally, being able to share detailed descriptions of a child’s cognitive and social behaviors during a conference and in other communications can help families better understand their child’s learning trajectory.

Developing a manageable system for taking and using anecdotal notes in the preschool classroom is the foundation for reflective practice and intentional instruction. A well-organized system frees you to focus on the children instead of on the “how to” aspects of record keeping. Notes with clear language, abbreviations, and evidence provide concrete documentation of children’s emerging behaviors, knowledge, and skills, and they also ground your ongoing reflective practices. This type of intentional, supportive assessment contributes to children’s learning and development.

4A.1 Show that your written child assessment plan describes how children are assessed (e.g., by whom; in groups or individually; timeline; familiarity with adults involved).

4B.2 If child portfolios are used as an assessment method, show or describe how the results are used to create activities or lesson plans.

4D.1 Show two examples of how information from an observational assessment you conducted was used to create an individualized activity.

4D.7 Show two examples of observational assessments you conducted, in which you noted a child’s strengths, interests, and needs.

Read more about anecdotal records in the longer version of this article, “Anecdotal Records: Practical Strategies for Taking Meaningful Notes,” in the July 2019 issue of Young Children.

Photographs: top of article © Getty Images; images within article, courtesy of the author.